Still Hurdling After All these Years

Still Hurdling After All These Years

Francis X. Shen

Originally written in February 2007 and updated in updated in 2012 and 2017 and 2022

When you’re almost 30 35 40 45, and you’re spending your precious free time doing hurdle drills and running 60 meter sprints with a 10 kg weight sled attached to your waist, you start to wonder: Why? Why, when I could be doing any number of other things less taxing and more relaxing, am I out on the track by myself?

To answer the question, we have to go back a few years. And by a few, I mean 30! – back to March 1993, when I went over my first hurdle as a high school freshman at St. Louis University High School.

***

When I signed up for track and field in high school, it was only because I thought track would make me a better basketball player. As a fifteen year old boy everything was basketball. Track was an afterthought, and I had never heard of the hurdles. Even when I started to do well in the hurdles, I was willing to give them up my junior year for other interests. (Thankfully a patient Coach May made a personal call and convinced me to come back out). I performed well enough in high school (losing only once my senior year) to catch the eye of some college coaches.

In college at the University of Chicago, I began to get a sense that the hurdles might be something more than just a scholarship ticket or an extracurricular activity. For the first time I met people who lived and breathed the hurdles. Coaches Ray Williams and Ed Wallace, along with head coach Jim Spivey, introduced me to the joys of track and field. Their commitment and energy rubbed off as I started to change my lifestyle.

While I changed many things, including more stretching and harder workouts, perhaps the most telling adjustment was my diet. Entering college I proclaimed my allegiance to the “red meat diet” – a diet where I would primarily eat red meat. I drank whole milk, and made it a point to tack on a hamburger and fries to most meals at Pierce Dining Hall. When asked, I used this analogy: If you’re walking, and you step on grease, you slip. So … all that grease in my body is just lubing up my veins, letting the blood rush through. When my friends told me this was the silliest thing they had ever heard, I countered that I was personally testing my theory in a scientifically rigorous manner: I had to eat all those burgers to see if my theory worked. The cheese fries were for science!

This changed when a friend gave me a copy of Dr. Michael Colgan’s book, Optimum Sports Nutrition. On page 7 is the line that stopped me in my tracks: “Athletes who scarf down fat-loaded burgers and nutrient-poor fries do not understand how much they are disturbing the exquisite precision of nutrient use by their bodies.”

Colgan’s book did more than just cause a change in my diet. Colgan made me think about deeper questions: why? Why was I training? What would I sacrifice for the hurdles?

***

After NCAA competition came to a close in my red-shirt fifth year at UChicago, the “why” question became harder to answer. In college I was young, without real responsibility, and had a chance to compete at the Division III Nationals level. I was training in order to help my team win a conference championship. I was training to see how much I could push my body, and how fast I could run the hurdles. Ask any college athlete why they competed in their sport during school and I imagine you’ll hear similar sentiments expressed.

After college I figured I’d give up the hurdles. I had given it my all, and now it was time to move on. The hurdles weren’t as important as the rest of the things I should now be doing. Or so I thought.

I had envisioned life without track as a life full of free time. Instead of spending nights at the track, I would spend them reading or working or with family. Instead of spending entire weekend days at meets, I would be able to do so many things I had never had time for.

But life without the hurdles turned out to be very different from how I had imagined it. It was the first time since I was ten years old that I was not involved in organized, competitive sports. Without sports to focus, I found myself wasting more time that I had before. Hours and entire afternoons seemed to disappear with nothing to show for it. I actually had less energy than I had when I was training full time. I missed the company of fellow “tracksters,” people who were also crazy enough to pursue their passions after college.

I tried to fill the void with all sorts of physical activity and hobbies. I spent more time in the weight room and thought about running an ultra-marathon. But try as I might, I couldn’t find a replacement. Pick-up basketball games and bicep curls weren’t cutting it.

By October of 2001 I was searching online for a Boston track club to train with. I was back racing over hurdles a few months later. Life without the hurdles lasted all of four months.

Why did I return so quickly to the hurdles? Certainly one reason was the productivity issue. Without track to organize my life, I wasn’t working as efficiently. But there was something more to it than some simple utilitarian calculus. This wasn’t just about costs and benefits. More than anything else, my return to the hurdles was about a longing for the intensity, energy, and adrenaline rush that that competitive sports offer.

***

I have frequently been described as “intense”. I pay attention to small details, and push my limits. This has something to do with the hurdles.

It’s probably true that to train seriously for any sport requires a good amount of intensity. This is certainly the case for the hurdles. Unlike the men’s league down at the YMCA, you cannot just walk onto a track and run a hurdles race. If you don’t go fast enough in the sprint hurdles you will find yourself crashing into a hurdle and falling to the ground.

Running the hurdles requires both refined technical skill and raw physical strength. Like golfers preparing for a putt, hurdlers must perfect their mental game. Like gymnasts, hurdlers must be able to train their muscles to contort in special ways. Like basketball players, hurdlers must have great spring in their step. Like baseball players focusing on a ball, hurdlers must be able to concentrate on each and every hurdle. Like football players, hurdlers must be able to achieve great strength. Like runners, hurdlers must have great endurance.

Hurdles is intense to begin with, and post-collegiate hurdling is all the more so because without many hurdlers around to train with, you can end up doing much of the work alone. You are your own boss. You must discipline yourself to push beyond the pain, to go out and practice when you would rather go out to the bar and watch a game.

In the 20+ years that I have been hurdling since my last college competition, I have spent many nights as the only person in the weightroom and many mornings as the only person on the track. On vacations and business trips, I always try to sneak out to the local track to get in a hurdles workout.

To some, perhaps to most, my love affair with the hurdles is a mystery. After all, I’m never going to run the hurdles in the Olympics, the U.S. Track and Field Olympic Trials, or even the USATF annual championship meets. I don’t get paid to run, and I spend money every year on training gear and meet fees.

Whether they say it or not, I think the most common response people have is a mix of shock (you’re still hurdling?!) and doubt (aren’t you too old to be doing that?).

***

The more I have thought about the hurdles, the more I have come to the realization that the hurdles are not an “activity,” but a lifestyle.

This is one of the reasons I gravitated toward the Greater Boston Track Club (GBTC) in the 2000s. Here, for the first time since college, were a group of people also in the track lifestyle. Here were people who understood the difference between “doing a workout” and “going for a run.” It was the track family I had been looking for, and it’s no wonder that when I was in town even blizzard conditions didn’t keep me away from our regular practices.

The big difference between “going to the gym” or “getting in some cardio” and what we do is the competition. When you line up to race the hurdles, you are not just there to get in shape or feel good about yourself. You are there to compete. You are there to do everything you can to beat the athletes in the lanes next to you. You may congratulate them afterwards, but during the race you are trying to beat them to the finish. It is the same instinct that kids have when they race each other on the playground: you want to win.

Racing is risky. Racing means you put yourself in front of the world, and even if the world isn’t looking, you’re exposed. If you’re out of shape or run a bad race, the clock will show it. There is no hiding. If you’re slow, you will be beat by others who are faster. If you don’t work hard enough, the athlete who works harder will pass you.

Training is also risky. You can train for months and with one pulled muscle have your whole season disappear before your eyes. You can hit a hurdle, or miss a step, and have your entire race thrown off. You are given one shot, and you can blow it. I know this because I’ve done all of the above. I’ve choked in big races, I’ve trained for months only to pull a hamstring, and I’m beaten all the time by hurdlers who are faster than me.

This is the difference between competitive sports and “going to the gym”. In the gym, you’re can’t lose. Gyms have televisions so you can forget about the running; trainers with you at every step so you don’t have to think for yourself; and guarantees that you’ll leave feeling great.

Hurdling does something else entirely. It humbles you. Hurdling isn’t a way to forget about the reality of life. Hurdling brings that reality front and center. Like other serious track and field athletes, hurdlers feel anxiety as they realize that everything hinges on one, short race. Hurdlers suffer the pains of disappointment and failure when they don’t perform up to expectations. Hurdlers don’t always walk off the track feeling great about themselves. Sometimes they walk off the track so disgusted and deflated they don’t know why they ever started doing it to begin with. Hurdlers get knocked down.

But the great lesson of hurdling, the great lesson of competitive athletics, is that you fight back. You feel the pain, but you work through it. You acknowledge defeat, but you don’t accept it.

***

If you have ever been a competitive athlete, at any level, you will understand the idea that the world fades away when you are in the heat of competition. On great kick-off returns, or magical basketball shots, instinct takes over. The same thing happens in the hurdles when you’re locked in: you just go.

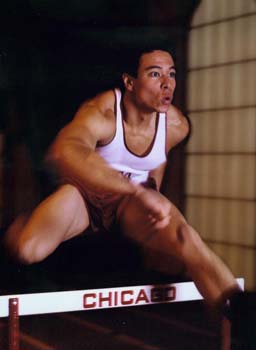

A teammate once took a photo of me warming up for a meet. It captures the essence of my pre-meet experience: headphones on, music blaring, focused only on running fast.

It’s not that hurdling is the most important thing in my life. It isn’t. My family, my friends, my work, and of course my Faith all rank higher. But hurdling is a part of all these things.

One thing I often do during warm-ups is turn to some spiritual prayer techniques I’ve been taught. (I’m a devout Catholic and have drawn many spiritual insights from the Society of Jesus, the Jesuits). During my warm-up, I will take a moment to think about all the graces that have happened in order for me to have the opportunity to compete. From my parents’ and coaches’ support, to the dedicated people who are running the meet, to the Founding Fathers who so many years set up this great country, to the opportunities I have been given professionally – I think of these things and I am grateful.

When I work, I frequently use track analogies. I tell myself on large projects that if I can just “get to 200” (the half-way point), I can turn it on and bring it home. I tell myself that I can learn new things with “consistent training over time.”

Crouching down in the starting blocks, listening for the commands (Marks, Set, Go!), knowing that you have one and only chance – it never ceases to make you nervous. Your heart beats faster and you focus with great intensity. You want to jump out of the blocks with every muscle in your body and ATTACK the first hurdle!

This is the feeling that no amount of cardio or spinning or going to the gym can produce This is what prepares you for all the “one time” chances in life: that one meeting you have with a client, that one moment you have to win over a crowd, that first impression you have to make.

This, as they say, is the good stuff.

***

I like to say that as long as someone keeps setting them up, I’ll keep running over the hurdles.

But when I first wrote this essay in 2007, I thought “that there will come a day when I do not hurdle anymore.”

15 years later I don’t feel that way anymore. I have had the blessing to become a member of the Masters Track & Field community: competitors in all events, ages 35-100+, still making it happen. (Find out more here and get involved!)

I have been inspired by watching athletes at 60+, 70+, 80+ and even 90+ do amazing things on the track. So long as these legs can do it, I look forward to being a part of this community for another 30+ years.

The hurdles for me are a gateway. In the Gospel of Matthew (Chapter 25: 14-30), Jesus tells the parable of the talents. In this parable, two servants bring back more than they were given by the master. The master tells his servant that because they were faithful with a few things, they will be entrusted with more. The hurdles are just a few things, but perhaps there is more to come.

And maybe, when it’s all said and done, that’s why I spent my nights doing sprints on the track. Maybe that’s why I’m still hurdling after all these years.

Maybe the hurdles I’m training for aren’t the plastic barriers I’ve been running over.